In 1962, an avalanche-turned-debris-flow destroyed nine villages near Yungay, Peru. Towns vanished in minutes, and the by the time it reached the river below, the loaf of debris was reportedly nearly 40ft tall and around 1 kilometer long, and carried bodies over 60 miles (BBC, 2004). Afterward, the Peruvian Geomorphology Commission of the Geographic Society of Lima concluded that significant risk remained and needed to be studied, and two American scientists went and analyzed the region, concluding not only was there in fact significant danger, but predicting an “ice fall and landslide” up to three times larger might come to pass, threatening Yungay itself. While their findings were published and initially discussed on a large scale, the region’s government demanded a retraction and took steps to forcibly prevent citizen discussion supportive of the prediction. The scientists fled the country not long after (Bryan Mark, 2007).

On 1970 May 31st at 3:23pm local, an earthquake struck nearby, shaking Huascarán – the tallest mountain in the Peruvian Andes – upon which Yungay is built, and triggered a glacial slide, which became an ice avalanche and rockfall of 7.5-25 million cubic meters – which rapidly picked up more matter to become a debris flow comprising at least 50 million cubic meters – soaring down the mountain at speeds perhaps as fast as 270MPH, and never slowing below 11MPH on its journey to the sea.

In the area of Yanamachico, upstream from Yungay, eyewitnesses reported that the arrival of the wall of mud was preceded by a wind blast so violent that “it stripped leaves, branches, and even the papery bark from the eucalyptus trees near their house, leaving them standing denuded “like telephone poles”

(Oliver-Smith, 1986, p. 4–5)

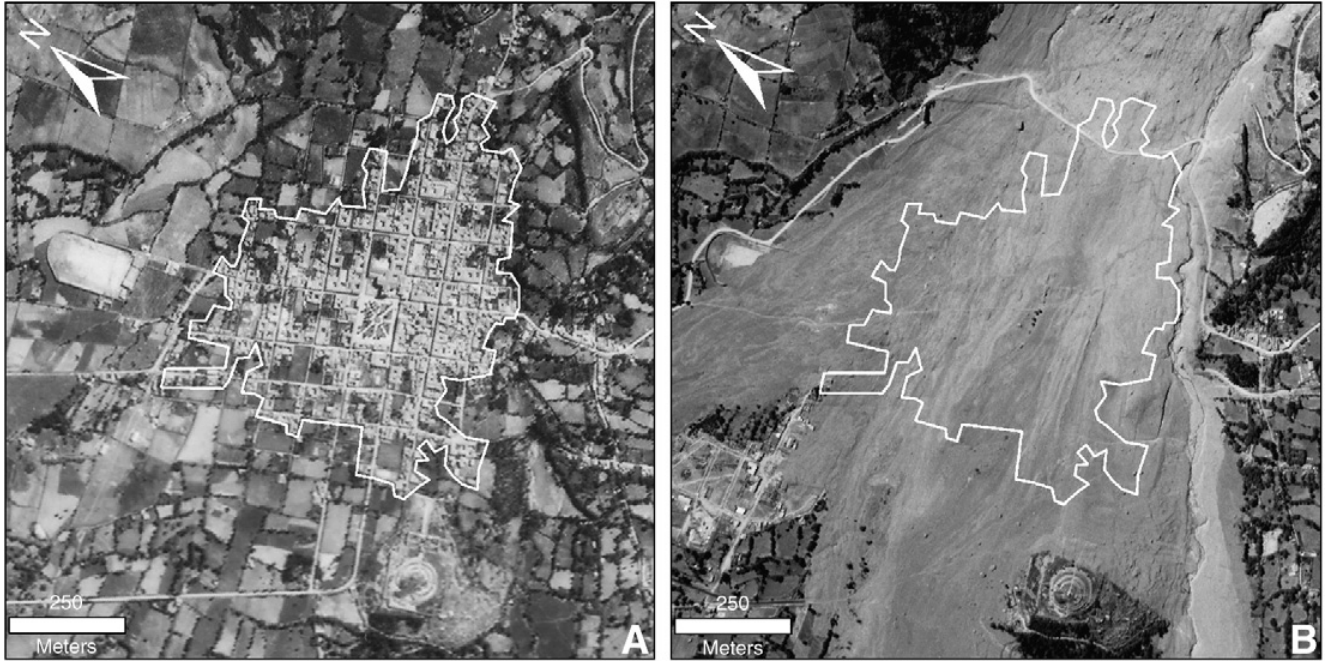

On its way down, a portion of the flow jumped over a ridge, went airborne for a brief moment, and collapsed back down onto Yungay, burying everything save for the top of a church, part of a bus, and a few tree tops. Estimates of the death toll vary widely, from as high as 30’000 to as low as 3’000, and this event became the most deadly glacier-related disaster in recorded history. (Lloyd Cluff, 1971; Diane Carlson, 2007; Stephen Evans, 2009; USGS, 1970; University of Oregon)

In keeping with the saying “Once a landslide, always a landslide”, in studying the region after the 1970 flow, the United States Geological Survey in partnership with Peruvian researchers found there had been an even larger slide in the area in the past, and the USGS report declared “Ranrahirca definitely should not be rebuilt at its previous site because of the danger of other debris avalanches originating from the north peak … and other small settlements along the lower part of the Rio Llanganuco that were destroyed by the Ranrahirca lobe also should not be rebuilt. Potential safe sites … can be found on the alluvial terraces just south of Ranrahirca and north of Yungay.” (USGS, 1970; Diane Carlson, 2007)

Following the disaster, many of those in the area resettled to the area north of Yungay, naming the settlement “Yungay Norte”. Out of concern there wasn’t enough space for the provincial capitol, the national government of Peru tried to resettle them to an area called Tingua, about 10 miles away. This was met with harsh, vocal, organized, and well thought-out resistance and Yungay Norte came to be renamed Yungay and is still the capitol to this day (Anthony Oliver-Smith, 1977). Additionally, the old town of Yungay has been declared to be a National Cemetery, and on the 30th Anniversary of the disaster, Peru declared May 31st to be “National Disaster Education and Reflection Day” (Annie Thériault, 2009)

Source Collection:

Annie Thériault, 2009:

https://web.archive.org/web/20110428055509/http://www.peruviantimes.com:80/31/yungay-1970-2009-remembering-the-tragedy-of-the-earthquake/3073/

Anthony Oliver-Smith, 1977 – All Pages:

https://wa.josh47.com/a/edu/natd/1977-OLIVER-SMITH.pdf

Bryan Mark, 2007 – Marked Page 111, PDF 12: https://web.archive.org/web/20100628235635/http://www.geography.osu.edu/faculty/bmark/2007%20Mark%20GPC%20offprint.pdf

Diane Carlson and Co., 2007 – Marked Pages 206-207, PDF 227-228 :

https://ia601300.us.archive.org/16/items/Physical_Geology_15th_Edition_by_Diane_H._Carlson_Charles_C._Plummer_Lisa_Hammer/Physical_Geology_15th_Edition_by_Diane_H._Carlson_Charles_C._Plummer_Lisa_Hammersley.pdf

Lloyd Cluff, 1971 – All Pages:

https://ds.iris.edu/seismo-archives/quakes/1970peru/Cluff1971.pdf

Stephen Evans and Co., 2009 – All Pages:

https://wa.josh47.com/a/edu/natd/Yungay1970MassFlow.2009.pdf

University of Oregon:

http://glaciers.uoregon.edu/hazards.html

USGS, 1970 – Marked/PDF Pages 8/14 – 13/19, 18/24 – 25/31:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1970/0639/report.pdf

©2023, Joshua Martinez – 2023/06/06

This report may be reproduced for educational purposes.

For other uses, please contact republishing@Josh47.com